Words and photos courtesy of Andrew Eberly

Fall is our busiest time for removing Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) and other woody invasives. When I scan the fields for plants to cut, Autumn Olive tends to stand out, but with the diversity of different forms and textures in some areas, even that species can blend into the background and go undetected. One eventually develops a search image for whatever the target species is. I tend to focus on the silvery and persistent foliage of Autumn Olive, or the barred pattern created by the compound leaves of Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia). When a single species or set of species comes into focus over the “background noise” of different forms, interesting patterns emerge.

An island of Swamp Rose (Rosa palustris) growing in a wet meadow in Fauquier County. Members of the rose family are often prolific cloners. It is likely that much of this island is just one genetic individual expanding outward each growing season. This area was burned in the winter of 2022. Islands of thorny shrubs like this act as a refuge and a food source for many animals. When planning restorations, it is worth thinking about how to lay out the landscape to accommodate for this growth form.

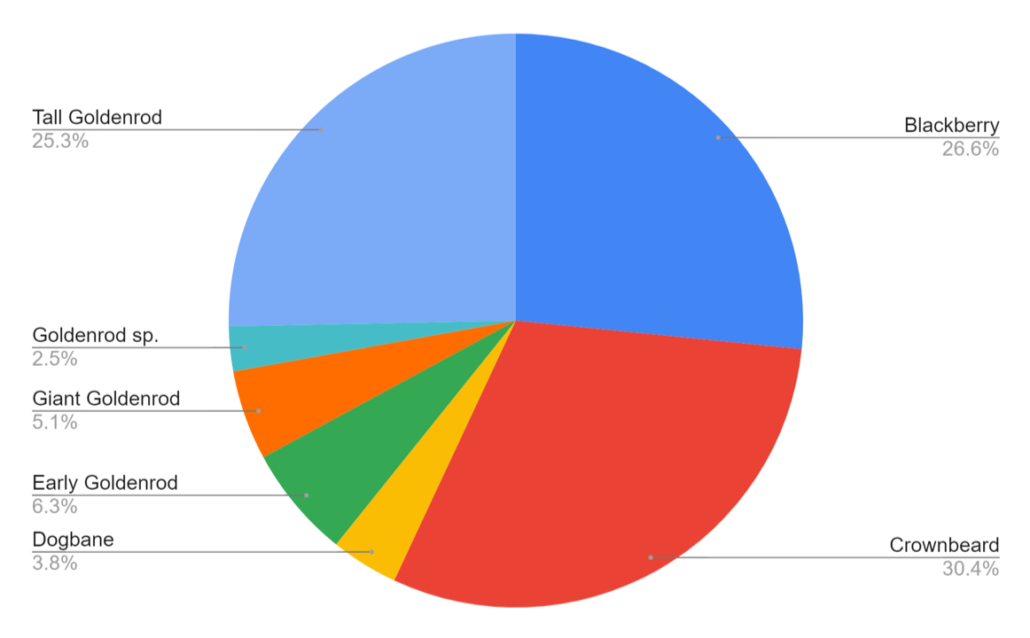

I often notice that many of the more prominent species seem to occur in clumps, almost like islands where one species is particularly dominant. The islands are numerous in some areas while absent from others. Occasionally, they even seem to have a ring-like shape. At Clifton, Blackberries (Rubus sp.) and Coralberry (Symphoricarpos orbiculatus) dominate patches of ground throughout the grasslands, Black Locust occurs as a few large islands of dense, thorny saplings, Sassafras (Sassafras albidum) seems to grow in mounds of evenly aged stems, even the Lowbush Blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum) of the forest floor forms islands that hold on to windblown leaves in the winter, adding to their bulk.

This is an interesting and familiar pattern. I am reminded of many other grassland ecosystems I have worked in: Wild Plums (Prunus sp.) and Sumacs (Rhus sp.) in the Flint Hills of Kansas, mounds of Mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa) and Shin Oak (Quercus havardii) on the Rolling Plains of Oklahoma, “mottes” of Live Oak (Quercus fusiformis) on the Edward’s Plateau of Texas, thickets of Turkey Oak (Quercus laevis) in a Longleaf Pine (Pinus palustris) savanna in Florida, rings of grasses like Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) and Blue Grama (Bouteloua gracilis) on dry prairies, walls of Alders (Alnus sp.) and shrubby Dogwoods (Cornus sp.) crowding stream banks in New England.

It seems to be a theme in ecosystems of many types, and I often wonder, are these really congregations of different individuals? Could the islands be just a single organism with lots of different stems emerging from one root system?

A large patch of Narrowleaf Mountain-Mint (Pycnanthemum tenuifolium) in Fauquier County. Like many mints this species is a master of spreading through rhizomes. This is also a prolific seed producer, it seems likely that a patch like this is expanding by both sexual and asexual reproduction.

Cloning in one form or another is a very common way for plants to propagate themselves. Many people may have heard of Pando, the Quaking Aspen (Populus tremuloides) in Utah that occupies 106 acres of land and has 40,000 above ground stems (trees) to its name. This is all a single genetic individual, connected by its roots to form the largest organism on the planet. King Clone is another famous clone, a Creosote Bush (Larrea tridentata) in the Mojave Desert that has been creeping underground and sending up new aboveground shoots for nearly 12,000 years. We have many local examples, indeed, most of our perennial grasses and forbs and many of our trees can produce new plants from some portion of their root system or underground stems designed specifically for cloning.

Several new shoots arise from a rhizome of Deer-Tongue (Dichanthelium clandestinum). This species forms clonal colonies in wet meadows. The rhizome has numerous roots growing form it and the purple area at the top is a bud where the cells that will become stems and leaves of a new above ground culm are waiting for warmer weather. If you remove the soil from a shovelful of turf from any given field you will notice that the top couple inches is full of rhizomes, all capable of sending up new shoots when conditions are right.

How do they do it? In many cases plants grow stems underground in addition to their aboveground stems. Underground stems are called rhizomes. Stolons are similar structures that hug the ground just above the surface. Rhizomes and stolons have buds at regular intervals from which new roots and shoots can emerge. Proper roots can also develop buds that become new aboveground shoots. Sometimes these underground buds take the form of bulbs like in daffodils (Narcissus sp.) or they emerge from thickened stolons like in potatoes (Solanum tuberosum). Aboveground stems that are members of a clone are called ramets.

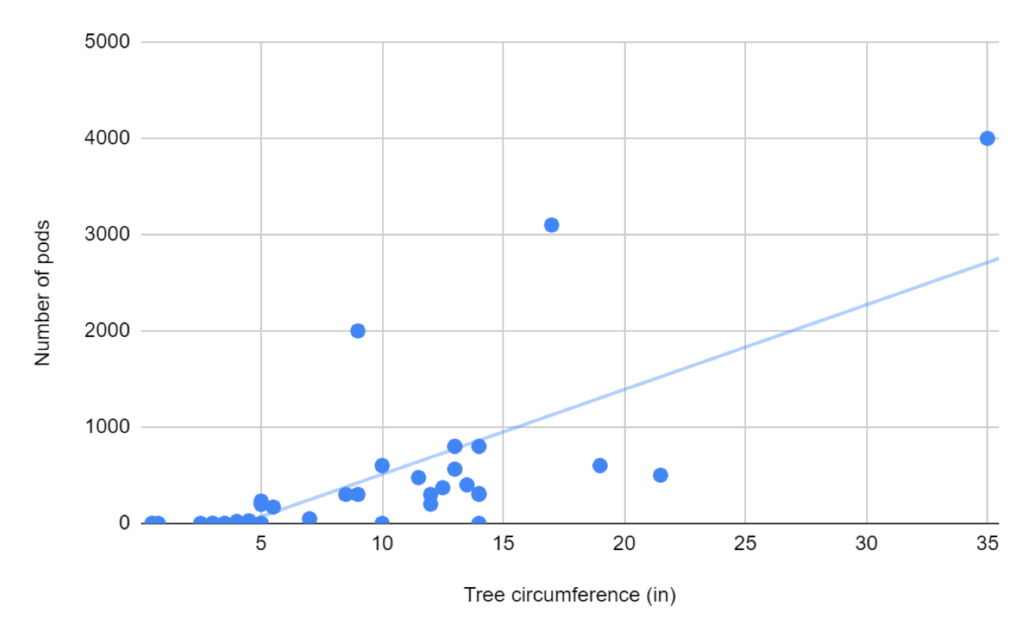

In trees, cloning is especially prevalent in species that grow in disturbed areas like Black Locust, Sassafras, and Sumacs. In places where I have cut younger, more vigorous Tulip Poplars and Oaks, a flush of new buds seems to appear out of nowhere right around the edges of the stump. It is common to see Goldenrods (Solidago sp.), Mountain Mints, Ironweeds (Vernonia sp.), and many other herbaceous perennials growing in clusters. Colonies of Winged Sumac (Rhus copallinum) may expand across our shrublands at a rate of several feet per year while colonies of Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans) expand slowly, preferring to cluster their short rhizomes in tight bundles.

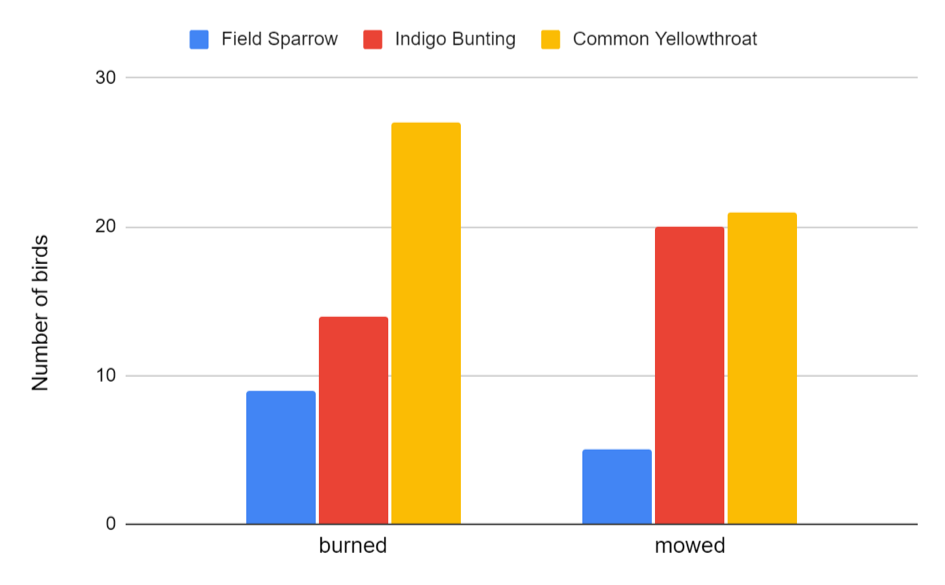

The ability to reproduce and spread underground has many advantages for plants that live longer than one or two growing seasons. When we burn or mow our fields in the early spring, we usually see a period of rapid growth afterwards. Most of this growth is generated by plants that may already be years or decades old, but were underground, where stored energy and protection from flames and freezing weather gives them a huge advantage over new seedlings.

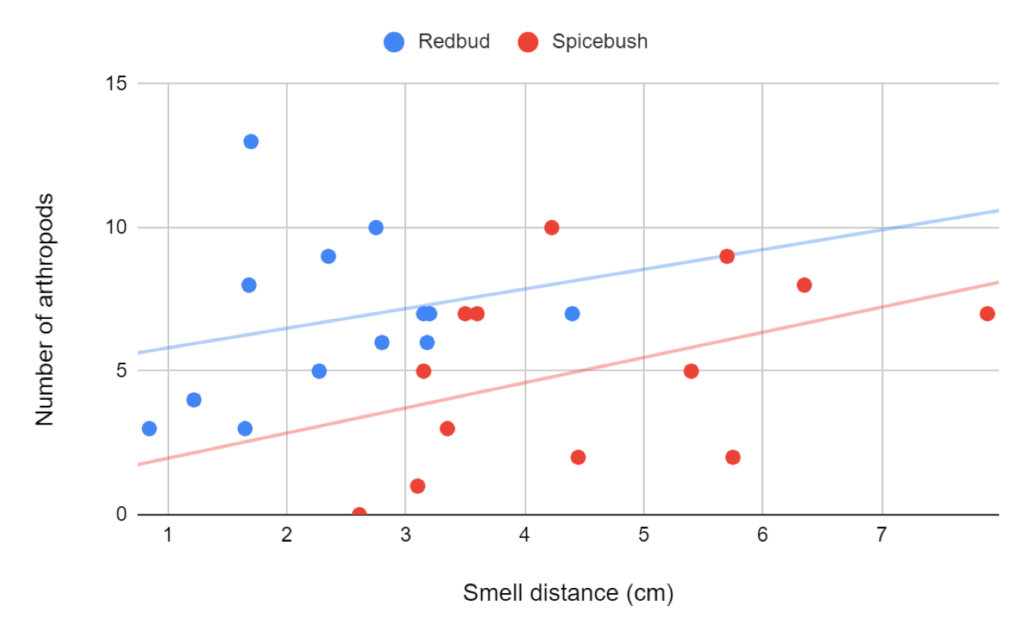

Underground growth also allows individuals to search for patches of resources like water and fertile soil, that may not exist exactly where the seeds originally fell. Old ramets on less suitable sites will die off, while growth becomes focused in new areas with better growing conditions, allowing the entire clone to shift across the landscape.

A particularly hot fire killed many of the mature trees here on Back Creek Mountain in Bath County. The Sassafras (Sassafras albidum) in the understory is a highly colonial species, capable of expanding quickly from existing rhizomes to form a dense shrub layer. Many of the Scarlet Oaks (Quercus coccinea) are also sprouting from the root collar adding to the diversity of this temporary shrubland.

If cloning is so efficient, why produce seeds at all? The evolution of flowers and seeds is arguably one of the greatest achievements of life on earth. I don’t wish to diminish the importance of producing seeds. Combining the genomes of two different individuals creates genetic diversity, spreads beneficial mutations and allows organisms to adapt to a changing world. Coating your offspring in a protective shell and then sending them off to the far reaches is a great way to colonize new lands and reduce competition. Once seedlings have established though, it makes sense that you would want to be able to keep sending up new versions of yourself in case one gets burned, frozen, eaten, or chopped down.

At Clifton we have a few American Plums (Prunus americana) that were planted in the South Pasture in conjunction with the larger riparian tree planting effort along a small tributary. Plums and many other members of the genus Prunus love to grow in the form of clonal islands, thickets of densely crowded stems that offer Quail and other grassland birds much needed shelter. We usually try to mow right up to the base of our tree plantings, but I have slowly been trying to give the plums and other plants that love growing this way a little space to develop new shoots or “suckers”. Even if the existing main trunk is girdled and killed, once the root system has developed for a few years, new ramets should happily sprout nearby.

I think it is important to consider this tendency of many species to spread by cloning in our management decisions. How does one accommodate for this pattern of growth when planning restorations or managing land? It seems many people tend to view patches of blackberries or single goldenrod species or any “monoculture” as a hindrance to diversity. This is not always the case; diversity happens on many spatial (and time) scales. For example, many clonal patches take on a ring-like pattern with age. As roots and rhizomes creep outward from the original point of establishment, they utilize available resources and with their combined energy, they can crowd out other plants. Over time though, ramets in the middle of the clone begin to die off as resources are used up and the plant basically out-competes itself. The middle of the clone then becomes bare ground where seeds of new species, with different resource requirements can thrive. Maybe this can be seen as a slow-motion disturbance event, creating new niches in the ecosystem while the clone anchors the soil and provides cover to pollinators and seed dispersers.