Most of us living in Northern Virginia naturally break down our region into sections based on geographic, ecological and cultural similarities. The Blue Ridge Mountains form an undulating wall on our western horizon, clearly visible for many miles as a rugged line of forested mountains. The coastal plain encompasses the lowlands surrounding the Chesapeake on eastward, across the Delmarva Peninsula to the Atlantic, and everything in between we call the Piedmont.

From a strictly geographic point of view, everything below the higher peaks of the Blue Ridge all the way to the coastal plain could be considered the Piedmont, which is defined as a gentle slope leading to the foot of a mountain range. But the Piedmont of Northern Virginia is a diverse landscape that can be a little hard to pin down under one umbrella.

The Piedmont is important. A line of big cities marks its eastern edge. Why? This is where ancient crystalline bedrock first emerges from under the young, low-lying sediments of the coastal plain. Wide, tidal waters easily navigable by cargo ships encounter constricted, fast-flowing streams winding between the rocky hills. Mills requiring high gradient waters for power could load their products right onto big ships and send them across the world.

From an ecological point of view, the piedmont is a land of relatively high biodiversity. A jumble of different bedrock types, spread across a landscape of rolling hills and meandering valleys leads to diverse soils. The Piedmont’s position just below and east of the mountains makes for a milder climate with somewhat higher rainfall than areas just to the west of the Blue Ridge.

When trying to define the Piedmont geologically, things get much murkier. In fact, one could easily make the argument that everything west of a line from Culpeper to Warrenton to Leesburg is actually part of the Blue Ridge Mountains. How is that?

The “Piedmont” in these parts is actually divided into three very distinct regions geologically. To understand that better, let’s look at things in a cross section. Since the whole region is oriented from southwest to northeast, we will start in the southeast and head northwest.

As you travel 17 north from Fredericksburg, you transition from the young, undeformed sediments of the coastal plain to massively deformed crystalline rocks just west of I-95. This is a land of choppy hills, and narrow valleys. The elevation generally runs from 200’ to 400’ above sea level. The rocks under these hills are from the early Paleozoic era, when there was little life on land and the dinosaurs were still 300,000,000 years in the future.

The current hills are the eroded nubs of huge mountains from that time. Many of the rocks came from far away and were smashed onto the edge of the continent as the seafloor was subducted underneath, like how a fallen log will collect rafts of foam from the surface of a river as the water moves underneath. In Northern Virginia, this band of low, rolling hills is part of the Inner Piedmont Province. There is an Outer Piedmont farther south and east in Virginia, but it disappears under the sediments of the Chesapeake to the north.

The rolling hills of the Outer Piedmont with the Blue Ridge Mountains beyond. Between lie the lowlands of the Culpeper Basin. To me this is the most characteristic landscape of the Piedmont.

Just past the community of Morrisville, the landscape changes abruptly. The mostly wooded hills are gone and a flatter landscape of broad agricultural fields opens up. This is the Culpeper Basin. A relatively new addition to the geologic landscape of Virginia. By new, I mean there were dinosaurs walking around, and big trees, but no Atlantic Ocean yet, when this basin came into existence.

The basin is the result of a stretching force on the earth’s crust, opposite the force that pushed the rocks of the Outer Piedmont onto the eastern edge of the continent. The Piedmont rocks started to break free and slide away from the Blue Ridge Mountains during the Triassic period some 230,000,000 years ago. The gap in between was filled with sediments to form a flat basin where lava occasionally flowed across the land. The area would have initially looked like a portion of today’s Great Basin in Nevada and Utah. No major tectonic events have occurred since then and the landscape you see today is basically the work of 200,000,000 years of weathering and erosion sculpting this once dramatic rift basin.

Death Valley is an extensional rift basin in Southern California. The topography is likely similar to what the Culpeper Basin looked like in the Triassic and Jurassic periods with the Blue Ridge on one side and the Inner Piedmont on the other.

Just before you reach Warrenton, the landscape changes again. Hills once again dominate the scene. These hills are somewhat broader and taller than those of the Inner Piedmont. They are the remains of lava flows that occurred more than 530,000,000 years ago. The lava was metamorphosed into the greenstone of the Catoctin Formation. This rock is very resistant to erosion and stands high in ranges like Pignut Mountain, where The Clifton Institute is located, and the Watery Mountains just to the west. If you were to stand on the summit of these hills and look northwest, Catoctin Greenstone would also form the higher ridges on the western horizon. In fact, it used to cover everything in between but has been removed by weathering like a giant ice cream scoop, to reveal even older rocks underneath.

Standing on the Catoctin Greenstone of Wildcat Mountain looking west. Catoctin Greenstone also sits atop the high ridges of Mt. Marshal on the horizon. The whole scene is part of the Blue Ridge Anticlinorium.

The rocks under these mountains originated along the eastern edge of North America before the Inner and Outer Piedmont terranes came crashing in and long before the rifting of the Culpeper Basin. The whole slab of rock between Warrenton and Luray was shoved westward some 60 miles from its original position when Europe and Africa collided with North America, detaching it from its roots deeper in the crust and forming what is called a thrust sheet. The whole unit is called the Blue Ridge Anticlinorium or just the Blue Ridge Province.

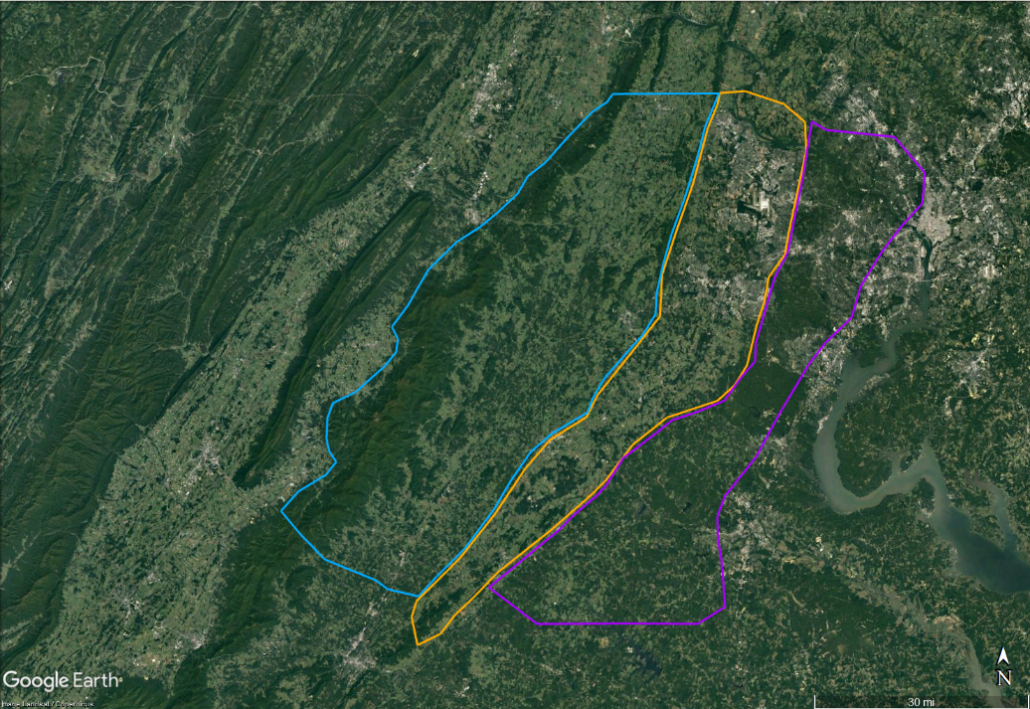

The 3 geologic divisions show up well on satellite imagery. The mostly forested hills of the Inner Piedmont (outlined in purple) are dark green. The lighter swath of farmland and urban development to the west is the Culpeper Basin (outlined in orange), dark areas in the basin are forests covering lava flows where the soil is too rocky for farming. The Blue Ridge Anticlinorium is a mosaic of forested hills and fields bounded on the west by the higher mountains of Shenandoah National Park (outlined in blue.)