We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Robert F. Schumann Foundation, BAND Foundation, and March Conservation Fund that makes this work possible.

What Is A Shrubland?

Shrublands are habitats that are between 3 and 20 feet tall and that are dominated by woody plants. In the eastern United States, shrublands occur when grasslands are allowed to grow up on their way to becoming forests. Shrublands appear in the Virginia Piedmont when fields are disturbed every 3-5 years. Unfortunately, most shrublands in Virginia are dominated by non-native plants, but we maintain 100 acres of native shrublands at the Clifton Institute by burning, mowing, and removing non-native plants. Our shrublands are a mosaic of shrub thickets, native grasses and wildflowers, and patches of young trees.

This is the Upper Woodcock Field, which is one of our restored shrublands. Here we removed non-native Autumn Olives and burned the field and the response from native plants in the seed bank has been remarkable.

The Loss Of Native Shrublands And Why it Matters

Historically, native grasslands and shrublands were widespread in the Piedmont of the eastern United States. These habitats were maintained by fires, from lightning strikes and set by indigenous people, that burned every three to six years. Bison and elk, both of which were once found in the Piedmont, also helped to maintain open areas. Unfortunately, these habitats have declined by more than 90% as a result of fire suppression, conversion to crops, urban development, and invasion of non-native plants.

Shrublands and grasslands host more declining bird species than any other habitat in North America. And shrublands are particularly threatened because they are often considered to be unsightly and they are hard to walk through and appreciate, unlike forests or grasslands. Shrublands are also a challenge to manage because the woody plants that create the desired habitat structure are hard to keep in check with either mowing or burning. Finally, shrublands are particularly vulnerable to invasion by non-native plants because they occur on the edges of forests. Non-native shrublands in the Mid Atlantic host 91% fewer caterpillars than native shrublands, which is bad news for birds, who feed thousands of caterpillars to each of their chicks.

Our research on Box Turtle habitat selection has revealed that shrubland-grassland mosaics at the Clifton Institute support very high densities of Box Turtles. Our data also show that shrub thickets serve as critical microhabitats for Box Turtles in northern Virginia.

The Solution

The right kind of disturbance at the right time

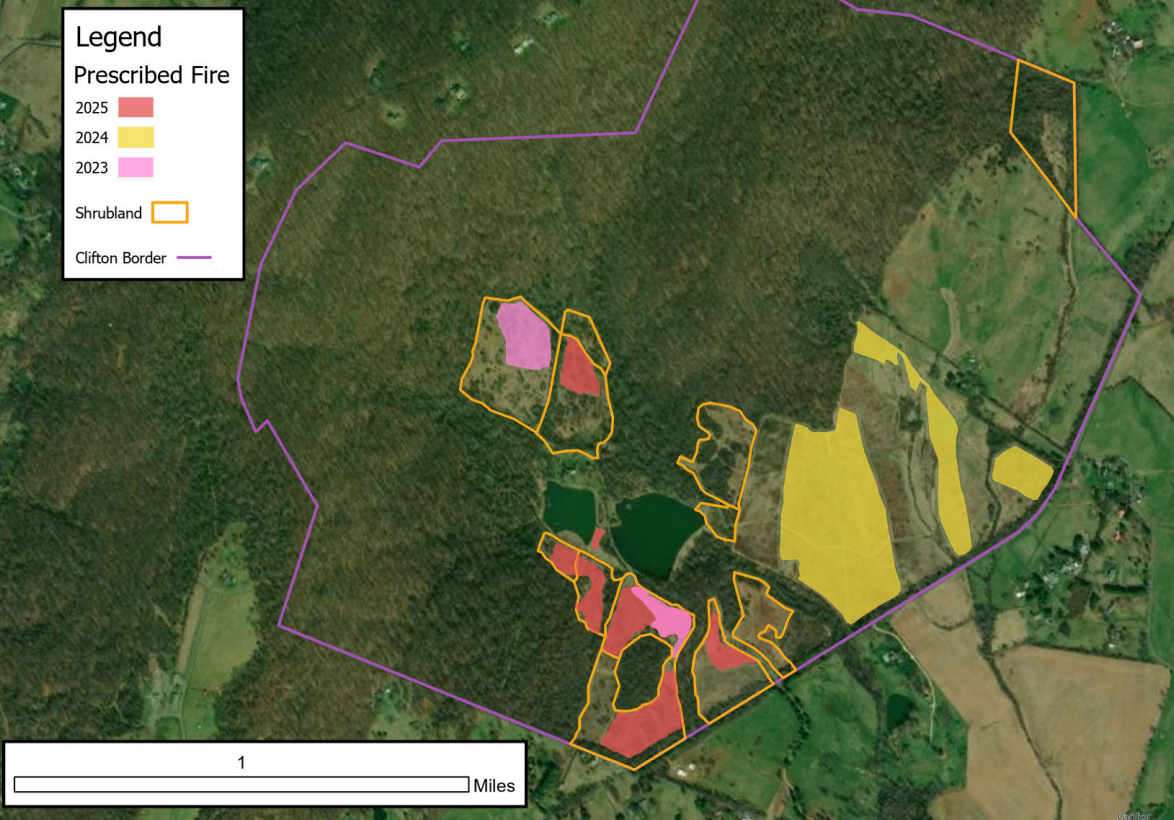

Most of our shrublands are disturbed every other year. But some areas are managed annually and others are left for five or more years. Whenever possible we use prescribed fire to manage our shrublands. Fire benefits native shrubland plants and controls non-native plants such as Tall Fescue that are not adapted to fire. We have invested in fire training and equipment, and we are able to do our own burns with the help of an incredible crew of volunteers. This gives us flexibility and enables us to burn approximately 50 acres per year. But fires are a logistical challenge compared to mowing, and it’s difficult to achieve a fire that’s hot enough to control woody plants. We use mowing (bushhogging with the tractor supplemented by walk-behind bushhogging in tight spaces) to maintain shrublands where fire doesn’t control woody growth.

Methods for effective control of non-native plants

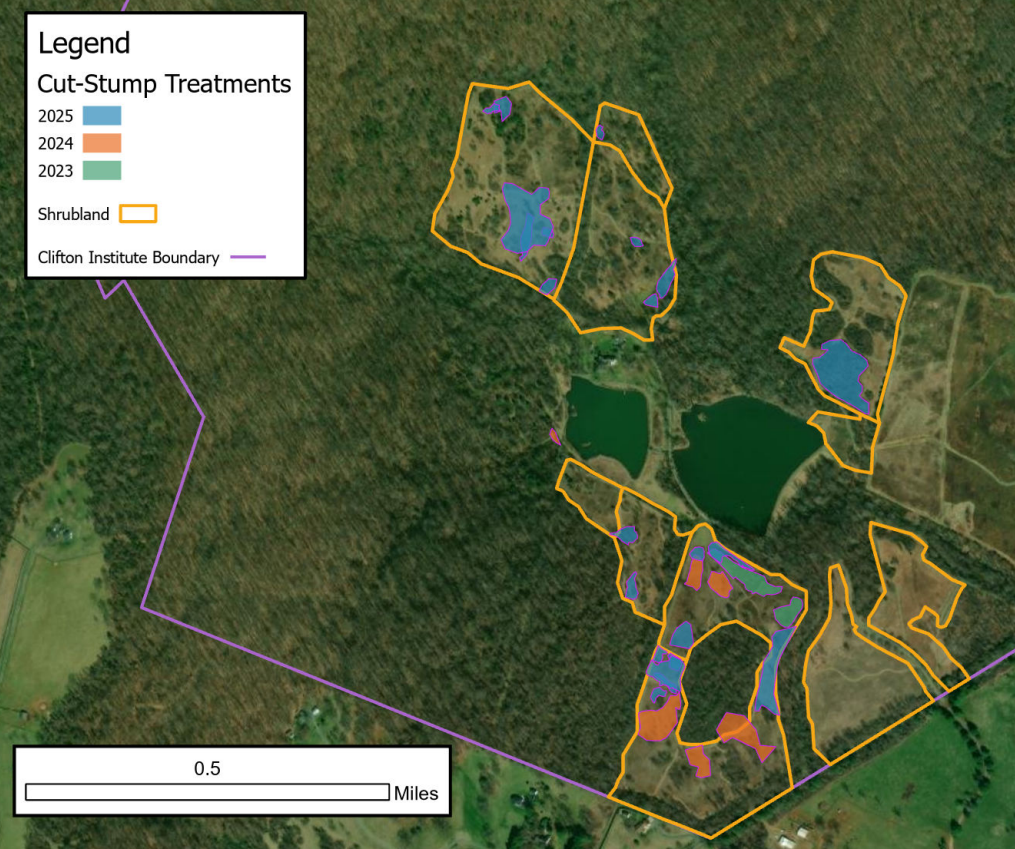

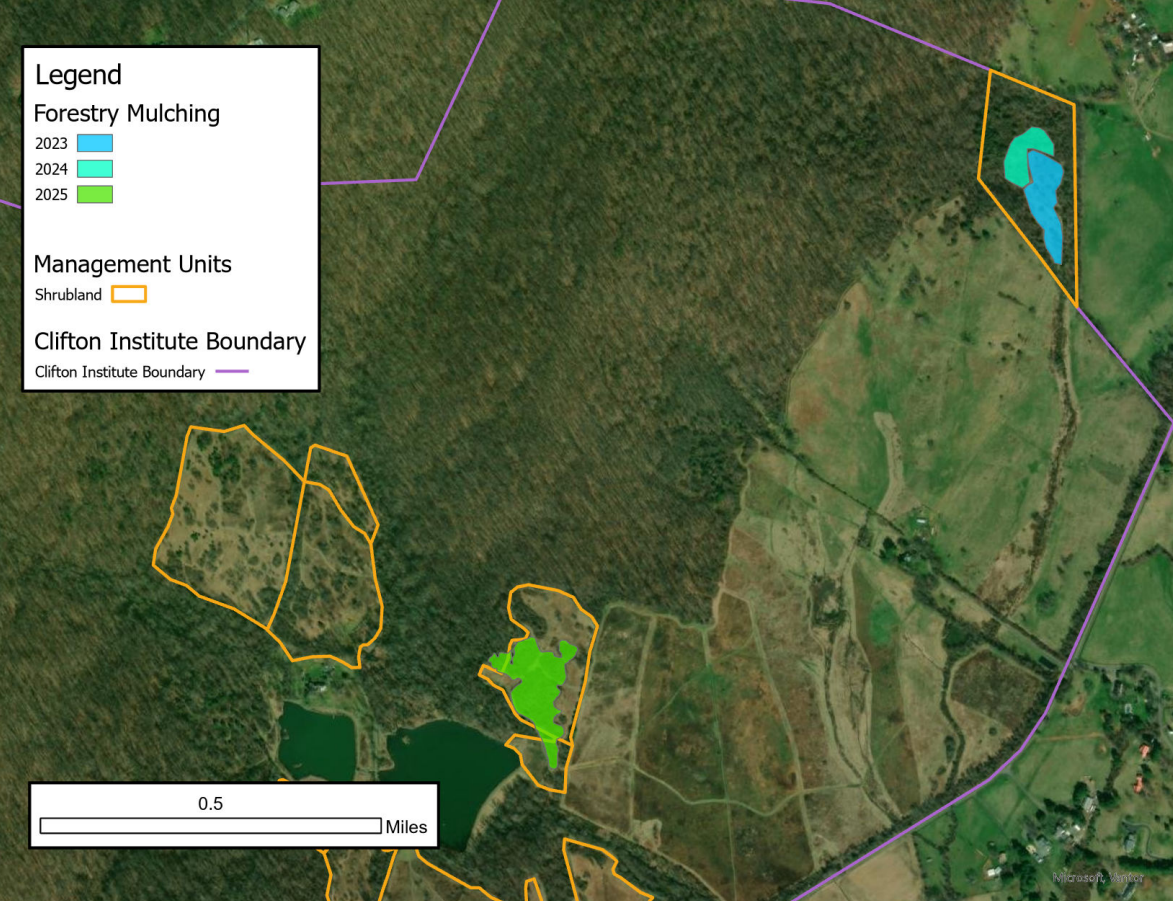

We control non-native plants by using a combination of mechanical and chemical methods, while always minimizing the use of herbicide. In the last eight years we have removed all of the mature Autumn Olives (the most prevalent woody invasive in northern Virginia) in our 100 acres of shrublands. In most areas we use a combination of cut-stump and basal-bark applications of herbicide to control Autumn Olive, Asiatic Bittersweet, and other woody non-natives. In fields that have not been managed in more than five years we use either a forestry mulcher or a skid steer with a grapple attachment to remove “old growth” Autumn Olive and restart the successional clock. We are also working to control Chinese Bush-clover and other herbaceous non-natives. This restoration work, that’s done by staff and committed volunteers, results in stable native shrublands that provide superior wildlife habitat.

Re-introducing native plants

In many cases the response from the native seed bank (viable seeds in the soil) is sufficient to re-establish native plant cover after we remove Autumn Olives. But when the natives need more help, we plant seedlings from our local-ecotype plant propagation program. We plant uncommon shrubs that we’ve found growing in unplanted shrublands such as Southern Crabapple, Dwarf Willow, and Allegheny Chinkapin as well as more common but equally valuable species like American Plum, American Hazelnut, Shrubby St. John’s Wort, Smooth Sumac, and hawthorns. And it’s not just the woodies. We re-introduce herbaceous species such as Hoary Mountain-mint, Pasture Thistle, and Elliott’s Bluestem as well.

Shrubland Restoration is Worth the Effort!

Since 2018 we have removed Autumn Olive and other non-native plants from 100 acres of shrublands. Some of these fields looked like a wall of Autum Olive when we started. But now most of them have been transformed into native habitats with abundant Smooth Sumac, Black Raspberry, Little Bluestem, and Slender Bush-clover. We conducted formal plant surveys in the Upper Woodcock shrubland after removing Autumn Olives. We found 65 species of plants in a 100-square-meter plot, placing the site in the top 5% of plant communities in the entire state in terms of diversity!